The recent election results have a lot of people discussing the effects the new administration will have on the rights of women, undocumented immigrants, POC and LGBTQ+ people. These concerns, however, are not the overwhelming concern that brought a Republican majority into the House and Senate. The main concern among most people seems to be the economy, and more specifically the price of goods. With the recent election, American River College students should expect to see a dramatic cost increase in the cost of goods, adding to the financial strain that many already face when trying to afford essential items.

Young people came out to vote for Trump in large numbers for the 2024 election, according to this NPR article. While their major concern seems to have been the state of the economy, as mentioned in a recent Gallup poll, younger people may find economic hardship affect them more prominently than those with established careers and income. While many of Trump’s economic policies expressed during his campaign may have seemed like the path toward economic security, young voters may find that these policies may not be the financial game changer they anticipate. The Trump campaign’s policy toward tariffs, in fact, may end up hurting younger people.

Students at ARC will feel the impact of these tariff proposals when Trump comes into office in 2025, provided they get approved by the House and Senate. With a Republican majority in both branches of government, it’s likely those policies will be enacted. Students at ARC should be aware of the influence that economic isolationist policies may have on their personal finances.

The first consideration will be the proposed tariffs to be applied to foreign steel and aluminum brought into the U.S. We already have examples of how a 25% steel tariff raised the cost of steel, which in turn caused a decline in domestic automobile manufacturing. New students transitioning from high school are almost universally new drivers, and the ramifications of steel tariffs will undoubtedly be an increase in the price of new automobiles. As Americans seek to balance their budgets and new car purchases decline, an increased demand for used cars should be anticipated.

Students are commonly in the market for used cars as they move from high school to college, and the results of a tariff will be an increased cost for those students with the increased cost of used vehicles. This will remove a chunk out of student budgets to need to subsidize vehicle purchase costs, reducing funds that could otherwise be allocated to other important student needs.

Moreover, maintenance costs will increase for these students two-fold. First, the increased costs of replacement parts often made from steel and aluminum will increase. Further, students will likely be forced to purchase older cars with higher mileage, as their purchasing power diminishes and the availability of affordable used vehicles decreases. This will result in more frequent repairs and part replacements for older cars, driving up maintenance costs for students significantly. “It doesn’t help that most automobile parts are manufactured outside of the U.S., and as such will be inversely affected by the tariffs.

If students then turn to public transit, they should also expect an increase in cost to be carried through increased pricing or municipal tax revenue. Once students get to their destination, they will inevitably need to worry over the rising cost of housing.

New housing construction is heavily reliant upon steel and aluminum. Steel provides the rebar that appears every 16 – 24 inches throughout all concrete, and the gauges vary depending upon the load bearing of the slab. Additionally, steel can be found in locks, door hinges and an array of other home construction related products. This cost will increase even before accounting for the construction and maintenance of the trucks required to deliver these materials to the construction site, which will have an adverse effect on the cost of less directly applicable construction materials.

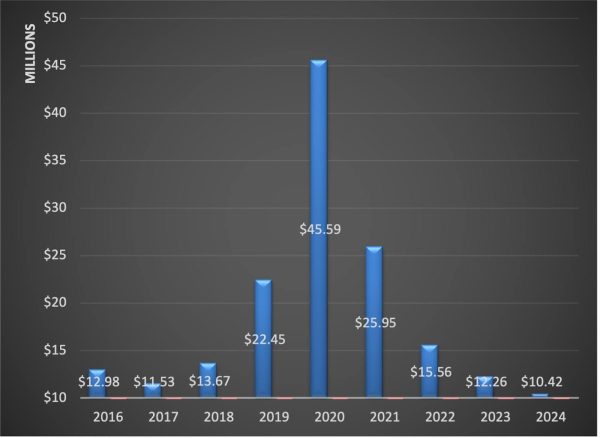

The graph above shows the cost of steel, specifically structural steel used in building construction, has grown. When the economy came back into full swing in 2021 following the COVID-19 pandemic, costs skyrocketed as tariffs limited the steel supply.

Students overwhelmingly rent as compared to owning their housing, and given that relationship with the real estate market, students should expect a lack of available rental properties. The cost of rent grew higher than home values through 2023, mirroring a trend that began in 2020. This comes at a time when rental costs are already a significant portion of students’ income.

Of course, exemptions can be made available for companies that require steel for production, as was seen in the 25% tariff applied by the U.S. Department of Commerce in March 2018 under the first Trump presidency. These exemptions, however, have been inconsistent in their provisions. Rather than being provided to companies that had a favorable sales-to-employment ratio, they were instead provided more frequently to companies that operate in states that supported Trump’s election and less frequently for companies that operate in states that were less favorable to Trump’s election.

Will these tariffs be compensated by a lower cost at the grocery store? Don’t bet the farm on it. Following the 25% increase in steel tariffs and the 10% increase in aluminum tariffs, several trade partners of the U.S. responded by enacting retaliatory tariffs on products like soybean and pork aimed as a direct attack on the American agricultural economy. This tariff war lost the U.S. an estimated $13.2 billion in the sale of agricultural products between mid-2018 through 2019, a U.S. Department of Agriculture economic research article states.

If the farmer stays in the production of food stores for Americans, but costs cause food production to suffer, it’s safe to assume based on precedent that farm subsidies will be the intended response. This means that the American taxpayer will need to foot the bill for the agricultural trade deficit in the form of a farm subsidy bailout. This had already occurred in Trump’s previous presidency. A whopping $52 billion were paid out by the USA to farmers in 2020, before Trump begrudgingly left office, an amount which hasn’t been paid out to farmers since 1933 amid the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl.

As the above graph shows, U.S. farm subsidies became a large expenditure following the 2018 tariffs, as exports to China and other trade partners were diminished through those nations’ retaliatory tariffs. Even now, China is preparing for another tariff war by lessening their reliance on U.S. agricultural goods.

Considering Trump’s record with taking care of his supporters following the steel tariff exclusions, it’s safe to assume that the American taxpayer will be footing an astronomic bill for farm subsidies yet again in order to compensate for aggressive economic policies.

Although these economic policies may seem like fresh ideas, they aren’t without precedent. The 1930 Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was instituted under the isolationist fervor that had enveloped American political spheres following the Stock Market Crash of 1929. The result of this tariff act were retaliatory tariffs from Europe, and is seen commonly as exacerbating the existing economic difficulties that were plaguing the country. History has not been kind to President Herbert Hoover’s mismanagement of the Great Depression, and it would be fair to assume that history may repeat itself.

The culmination of all of these factors spell economic difficulties for students who are already facing financial insecurities. Under the second Trump administration, ARC students should continue to anticipate a lighter wallet and less purchasing power as they attempt to balance their budgets while navigating higher education.

This article is the first in a multi-part series.