Everyday, the English language shifts and changes, with new words being introduced and old ones changing. This constant movement makes it one of the most complicated languages to learn. For those who already speak it, learning another can be an even bigger challenge.

“In Europe, learning a foreign language is a given, but in America, students are not exposed,” said Esther Martinelli, who is an Italian professor at American River College.

Kayla Countryman, a psychology major, found that learning a language requires consistent practice and discipline. “I tried to study Spanish, but I missed one day (of class) and that threw everything off.”

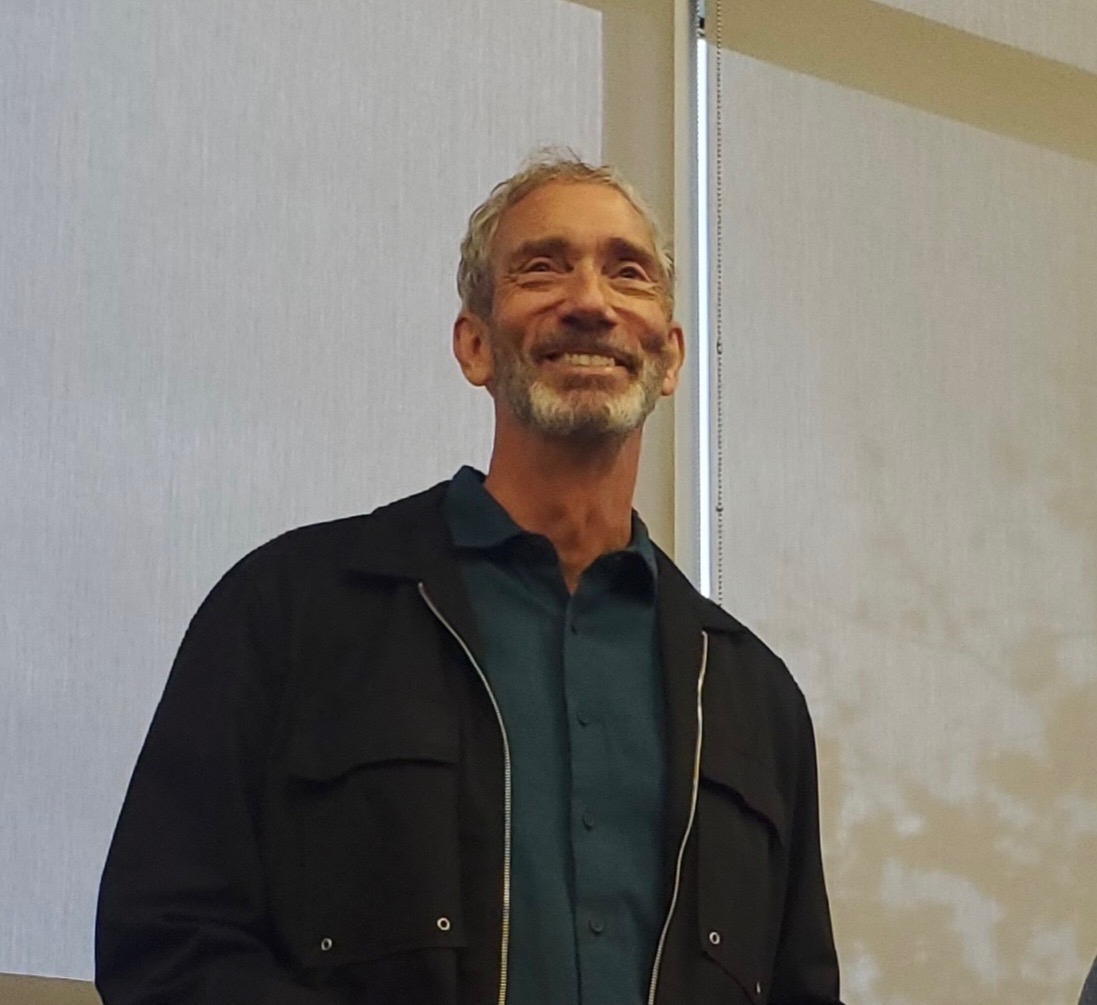

While learning a new language may seem like a near impossible task, David J. Peterson creates constructed language (conlang) from scratch.

Peterson is best known for creating the fictional language of Dothraki, featured on the HBO television show Game of Thrones, which is based on a fantasy book series, A Song of Ice and Fire by George R.R. Martin.

Dothraki is a spoken language that is used by a nomadic people that shares their name with their form of communication.

Game of Thrones takes place in a fictional world that has a large cast of characters and settings. Dothraki is a spoken language that is used by a nomadic people who share their name with their language.

Fictional languages, such as Dothraki, are languages that are used as if they are real by fictional characters. Klingon is the most popular example of this, which is used in the science fiction television series Star Trek.

“The grammars are complete,” Peterson said. “The grammar is there, can handle any kind of construction, and can theoretically translate anything. But it’s not necessarily going to have all the vocabulary that you’re going to need to cover that.”

Peterson begins the creation process making a conlang with how a language sounds.

“Usually I start with the nouns and move into the verbs, then onto more complex bits of grammar,” Peterson said. “Sentence structure, relativization, coordination, question information, things like that.”

One cultural example of how a language is shaped by the user’s environment is that the Eskimo language has 50 different ways a speaker could refer to the concept of snow.

“If you’re creating a language for a fictional people, say they’re just basic humans, then the language should look like it belongs there,” Peterson said.

But creation is not necessarily an easy track to fluency. When asked if he speaks every language he’s created, Peterson immediately responds. “Oh no – I mean, I’ve never studied them. It’s a different thing to create a language than it is to study it.”

Dothraki is one of Peterson’s best known works, but it came to him minimally. He started with 56 words already existed in the original novels.

“The first thing I had to do was determine what grammar was present there, because then that needed to be part of the grammar I was creating, so that everything in the books was still okay, still grammatical.”

“It should look like the other natural languages we have on the planet, in which case that brings in a whole host of other considerations.”

Languages should never be built for ease, or alternatively, immediately bogged down with too much vocabulary.

Just like with many other things, what you start with changes what you’ll end up with.

“That top level goal really radically alters your focus, and guides what you do down the line. Once you’ve got that, it really sends you down a path. If it’s a spoken language, I usually start with the phonology and its purpose. I like to start there and have that nailed down before I start doing things like making words and working with the grammar.”

There are some languages that have no need for a grammar structure, or even words at all. They can be entirely glyphic, written only in symbols.

In many cultures, the first exposure to a new language was through missionaries, who came bearing roughly translated bibles. When a word didn’t exist in the native language, it was pulled from English, beginning the embedding process that eventually normalizes it into everyday vernacular.

So is Dothraki a complete enough language that is possible to translate complete works such as William Shakespeare’s Hamlet from English to Dothraki?

“I mean, yeah it’s possible, but why would you do it?” Peterson said. “You could, but there’d be a ton of borrowing. There’s no real point to that. ”

Many argue that language equals culture, so it must equal mindset, but Peterson believes that is not always the case.

“Certainly, to an extent, but not to as large an extent as some might argue. I’ll say the one thing though, that I’ve noticed. If you speak only one language, and that’s it, you have one idea of how language works. Not just your own, but language period. The second you study another one, your entire understanding of what a language possibly can be is altered dramatically.”

Oftentimes, because it’s something new, people believe foreign languages are beyond their grasp, or out of their skill set. While teaching her first conversational Italian class, Professor Martinelli experienced something similar. “This conversational class really made me realize – we don’t always know what we’re good at.”

In closing, Peterson said, “It’s almost like a game, because that’s what a language is. It’s a system, and that’s all games are really. So you’re just learning a new system, a new way of solving a problem of communication.”