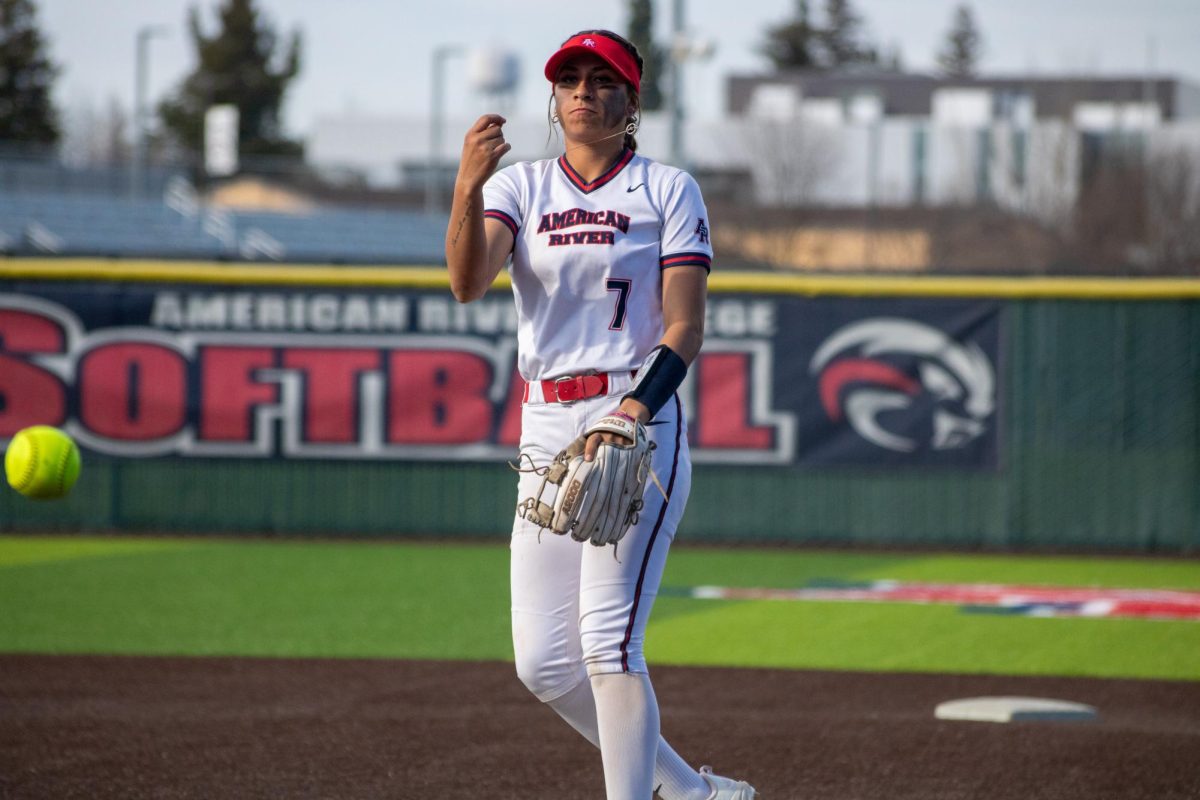

Any time a college professor retires, they leave behind a legacy. When American River College’s adaptive physical education professor retires in December, she will leave a legacy that initiated a transformational program for the lives of disabled students and an impact on anyone else who knew her.

Raye Maero, the adaptive physical education professor and women’s golf coach at ARC, renewed the adaptive P.E. program in 1996. ARC didn’t have an adaptive P.E. program for a long time and they hired Maero to restart it.

Brian Sprinkel, an instructional assistant who has worked for Maero for 13 years, stood in the adapted weight room and says that this is her legacy. According to Sprinkel, the adapted weight room wasn’t on campus until Maero wrote a grant for it.

Maero says she taught adaptive P.E. in K-12 schools for many years in Southern California. She earned a master’s degree in Adaptive Physical Education at California State University Long Beach in 1992 then relocated to Sacramento and worked as an interim professor at Sacramento City College.

“I just feel lucky that I had the chance to have this job and be a part of so many awesome people’s lives,” Maero says.

Maero says she enjoys working among the culture in community college and with disabled communities. She says she sees transformation in students who didn’t know they could even take a P.E. class, and pretty soon, they would have an associate’s degree.

“That is really inspirational to me – working with people who are beginning their journeys to learn what they need for a positive lifestyle,” Maero says.

Nisha Beckhorn, a coordinator and counselor for ARC’s Disabled Student Programs and Services (DSPS), has known Maero for 17 years and worked with her for three years. She says Maero was fundamental in the development and initiation of the program.

“A lot of programs throughout the state are getting rid of their programs, but we want ours to grow,” Beckhorn says.

Maero and her staff are excellent to students at DSPS, according to Beckhorn. The students set goals, achieve them and make progress. Beckhorn says Maero’s adaptive P.E. program supports the different levels of academics very closely.

“If a student in a wheelchair tries to sit and take notes for an hour, they need to build their strength to sit that long,” Beckhorn says. “When they are physically strong, they can take courses and keep their strength to walk across campus.”

Allison Murdaugh, a computer science major, takes Maero’s adaptive weights class to improve her posture in her wheelchair. Murdaugh says she has taken Maero’s classes for more than 20 years since the program started in 1996. She is in her chair upwards of 18 hours a day and the exercise helps her stay in her class, she says.

“If I dont work up to where I can stay in my chair for an extended period of time, I have to build up that stamina to sit in a regular class,” Murdaugh says.

Throughout her career, Maero says she has seen students walk for the first time and transition out of a wheelchair after taking her classes.

“I knew one girl who was uncomfortable being in the crowds at the cafeteria and taking classes here helped her deal with the size of the campus,” Maero says. “It enhanced her life, and to see people grow like that is inspiring.”

Maero says that to successfully teach the class, she has to step outside the box and be able to adjust on the fly. Empathy is an important characteristic for Maero; not that she feels sorry for the students but that she really understands their problems and experience.

Maero says she has modeled curriculums that mirror the general population and tailored them for disabled populations.

“If you’re in a wheelchair or can’t keep up with a sports class, we have lifetime sports, where you don’t have to wait on the sidelines — you can be the star,” Maero says. “We made a self-defense class for people with disabilities and that’s the best thing ever because people take advantage of people with disabilities and they have more sexual assaults than the general population.”

The adapted weight room is the only building on campus that has adaptive physical exercise equipment that is specialized for people with disabilities, according to Sprinkel.

“[Maero] has made it her daily goal to help this program succeed,” Sprinkel says. “Without [her], this program couldn’t be where it is at or where it is heading. She has the students’ interest first.”

Sprinkel says the program gives disabled students a place that is free of judgement.

The necessity for the program is understated and the type of people it takes to serve this community is very special, Sprinkel says. According to Sprinkel, they have qualities that can’t be taught.

“We treat [the students] with respect and support them with a strong environment that they can come to and feel supported, but also improve the social aspect,” Sprinkel says. “They are treated equally, like anyone else.”

Maero doesn’t know what professor will teach the class after she retires.

“I’m hoping with all my heart that they hire someone to take my place and [the administration] still think it’s important that students with disabilities have a quality physical education program,” Maero says.

Beckhorn says she has told Maero not to leave the program behind.

“If she has to retire, we will continue what she started,” Beckhorn says. “I feel like [Maero] has lived adaptive P. E. at American River College and we have to make sure that we support the program and help the program grow even more, so that [her] legacy lives through this program.”