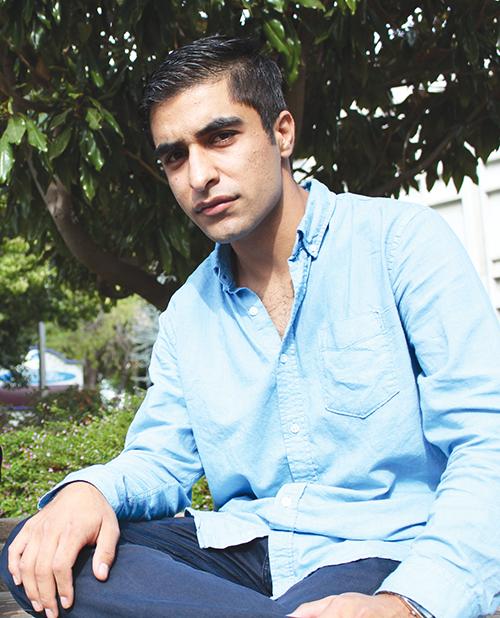

Unlike some of his peers at the VRC, retired Army Sgt. Michael Monk, 27, never wanted to leave the service.

Monk had wanted to be a soldier for as long as he can remember.

“Some people want to become doctors, firemen. … I wanted to be a soldier,” Monk said.

Monk describes his former role in the military with a large dose of humor.

“Ever watch the movies and see that a—— with the radio on his back calling a lot, and he tends to get shot? (I was) that guy.”

Monk was deployed three times during his seven years of service—twice to Iraq, and once to Afghanistan.

Monk said that his day-to-day job while deployed consisted of “house-to-house raiding, looking for weapons and people who didn’t like us, patrolling, trying to help repair the infrastructure.”

While deployed, Monk was seriously harmed by an explosion. Monk recounts the incident with a deadpan delivery.

“Afghans and Iraqis don’t like you very much. I thought we were gonna play freeze tag, they said, ‘We’re gonna hit you with a bomb,’ bit of miscommunication there. Did not get the memo.”

Monk was left critically injured after the attack. The Army later deemed him too injured to serve and retired him. Monk disagreed with their assessment, saying he was only “moderately hurt— some burns, some nerve damage, minor details.”

After being discharged, Monk, who was also recently divorced, didn’t know where to go or what to do. His grandmother stepped in.

“I was sitting in the Jeep with a dog, and shit, ‘What do I do now?’ I called grandma, she said, ‘You’re gonna go to AR, go to Sac State, go to McGeorge and become an attorney.’ ” he said. “That’s what she did.”

Monk’s transition was made more difficult by the loss of the rigid Army structure.

“I didn’t talk to anyone. The culture of values were so off. … (In the Army) there’s a hierarchy, there’s a structure, and all that’s out the window when you’re gone. There was something on every person’s chest and hat telling you how to treat them, and now that’s gone. It’s very confusing. You lose your position, all sense of self,” Monk said. “When I first came out, I found the VRC. If it wasn’t for the VRC I’d have been turned away.”

Furthermore, Monk explains, other students often made the adjustment process more difficult by showing a lack of tact when asking questions and making assumptions.

“The questions you always hear from civilians: ‘Ever kill anyone? Have PTSD?’ F—ing consistently.”

Monk’s breaking point was averted when he found the VRC.

“Roger (a VRC employee) listened to me, said ‘Alright, you’re stressed out, but we’re gonna help you. Done ranting? OK, now fill this out.’ It wasn’t a judgement thing. People weren’t turned off by the swearing, the frustration, because they understood it. You’ve lost everything. Your job, your sense of self, everything you used to be is gone.”

Monk now works with Avegalio at the VRC as a work-study while majoring in English at Sacramento State. He cares deeply about helping out other vets.

“I like to find other vets with the same issues and take care of them. Dan (Avegalio) is good at teaching ‘how to people’ again. We call it ‘peopling.’ ”

As for civilian students, Monk has advice on how to treat the vets in their classes.

“Ignore the aggressiveness. We’re normal people. Treat them like a person.”