The only person of color in the room. The oldest student in your general education class. The only stay-at-home dad at the preschool roundup.

Most of us have had some sort of immersion experience, where we’ve felt out of place, confused and maybe a bit scared.

At the end of that experience, though, the person of color, the nontraditional student and the male primary caregiver can often fold back into the familiar and return home.

Many of our English as a Second Language students don’t return home, or if they do, they discover something has changed. Maybe it’s the country they left. Maybe it’s themselves.

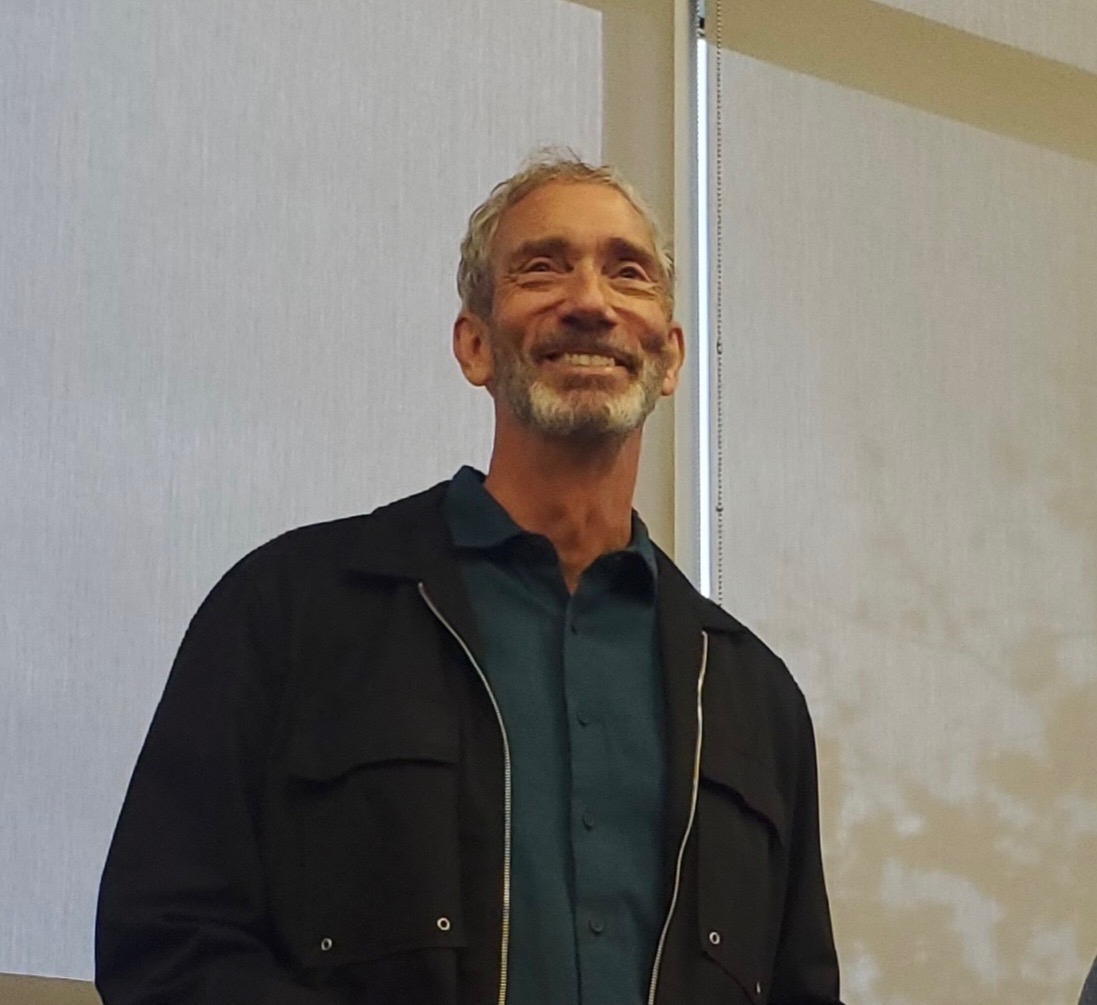

“When I lived in Ukraine, I was afraid to live in America,” said Peter Sukhin, an ESL student at American River College.

Sukhin said he had learned from the media in Ukraine that America was “bad.” When he first moved to the states, he said, he didn’t understand why people were smiling at him and saying “Good morning.”

Sukhin developed depression, and returned to Ukraine after living here for a short while. But as soon as he stepped off the plane, he felt “like a stranger,” he said. He had changed.

Even so, Sukhin said he still identifies as Ukrainian.

“I was born in Ukraine. That’s why I belong totally to Ukraine. My values, ideas,” Sukhin said through translator Olga Cuzeac.

International students often have trouble finding a place to live when they come to the states, and need to secure jobs where they don’t have to speak English right away. Many of them have families to support, so economic stability becomes the priority, even if the academic improvement is what prompted them to immigrate.

Many also carry the political burdens of their homelands.

“Very sadly … we have a lot of students who find themselves in … stressful situations,” said Allyson Joye, ESL professor. “We have Iraqi students who ended up in Jordan in refugee camps for months or years before they were able to get here … some of them left businesses, homes, just everything.”

Some students are afraid to return home.

Cuzeac said she has purchased plane tickets for herself and her young son to go back to her home in Moldova. The trip will require she travel through Ukraine.

“I feel awful,” she said about the conflict in the area. “I’m afraid for my son.”

Others, like Sukhin, are caught in the middle of family disputes thousands of miles away.

Sukhin’s parents divorced when he was a teenager. Now his father and brothers live in Moscow, while his mother stayed in Ukraine. The family has been emotionally burdened by the recent Russian invasion in Crimea.

“Father said to me, maybe two or three months ago, he said ‘Peter, Russia doesn’t need Crimea.’ I said to my father, “But why then (did) Russia put their armies in Crimea?’ Father said to me, ‘TV lies. There is no Russian military in Crimea.’”

“Two months later the Russian Federation annexed Crimea,” said Sukhin. “After, I said to my father, ‘So what?’ Father said to me, ‘My son, I don’t know what happened, I watch news from Russian Federation, what they said, then, I said to you.’ My father is shocked.”

Sukhin said his father doesn’t know who to believe now, and that his cousins and brothers won’t speak to him because of their differing political opinions.

Sukhin started having heart trouble, and was treated in hospital for a suspected heart attack.

“You … occasionally see stuff like this when someone is terribly distracted,” ESL professor John Gamber said of Sukins’ health problems. “And you sort of have to tease out why they’re distracted … Sometimes it’s simply that the load is too heavy, and if the load is already too heavy, it doesn’t take that much to send you over the edge … Let’s say you’re already just barely keeping track of your work, your family and your school stuff, and now you’ve got one more thing. It doesn’t matter what order it happened in … It’s that last straw.”

Sukhin said he is now good to stay here, but his decision to move to America wasn’t without significant consequences.

Sukhin met his wife when she was serving in Ukraine as a missionary for her church. She was born in Ukraine, but had lived in America for nearly two decades. The two hit it off and started communicating via skype when she returned to her home.

At the time, Sukhin was attending the University in Odessa and as she was making documents to call him to the U.S., he was two months away from receiving his degree in electrical engineering.

Sukhin had to choose right away: America or the diploma.

“(A) teacher said, ‘Education you can get in America, but if God gets you a wife right now, you have to choose your wife,’” said Sukhin.

Sukhin and his wife now have two young daughters. He speaks to his former wife and their teenaged daughter, still living in Ukraine, via skype.

Sukhin hasn’t been completely without support during his stay here. He is one of many Ukrainian students on campus and in the Sacramento area.

“(The) Ukrainian community has been here for a really long time,” said Joye, “and so they have a much broader network and there’s quite a large network of churches that help new immigrants and help them get on their feet.”

Short-term counseling is available in the counseling center, and “when there are language issues, we try to match (students) with someone who speaks that language,” said Rod Agbunag, counselor.

But, he said, “at the end of the day it’s going to be academic.”

Sukhin misses his family and has tried to help his father immigrate. In the end, though, Sukhin said the U.S. won’t open his father’s visa because they don’t want an “old communist.”

“My heart is crying,” he said of the conflict in his home country.