My career choice of writing and journalism has required that I pay attention to current events. When it comes to a subject like artificial intelligence, there’s been quite a bit of fear-mongering, with some of it being valid.

Unknown fears challenge contemporary truths, such as the current debates over creative license, more specifically the argument about AI using an artist’s work within its algorithm, usually without citation or compensation.

Every advancement in technology comes with its own set of unique difficulties that cloud established ethical standards.

When we discovered the automobile, we also discovered vehicular manslaughter. When we discovered the internet, we experienced the implosion of industries like music distribution, retail shopping and my beloved journalism.

We can study and hypothesize about the outcome, however we can’t accurately prepare for these outcomes unless we operate under assumptions.

When technological change lands upon our shores, careers may disappear as the future becomes the present. One of the earliest examples stem from the beginnings of commercial manufacturing, during the early stages of the Industrial Revolution in England.

Then, a group of artisan textile makers were found to be roaming the countryside, smashing newfangled water mills used for more efficient textile manufacturing. This was done as a form of protest for those mills taking their business. The name of those rebellious artisans was the Luddites, named after their leader Ned Ludd, and the group’s name has since become synonymous with resistance to technological advancement.

As a writer, thinking about the Luddites during the emergence of AI gives me something to consider. Will AI render my job obsolete?

Since these concerns seem to be omnipresent in the vernacular of the American experience, I would like to use this opportunity to highlight the limitations of AI in its capacity to duplicate human interaction.

AI is not as intimidating as it’s been made out to be, and the examples are right under our noses.

Let’s start with the big drawback that currently exists with AI: that people don’t like dealing with someone or something they can’t relate to. When I hear people complain about AI chatbots, I’m reminded of the same argument being put forward about call centers based out of India.

The complaint was the same in both instances, that the information the consumer is trying to solicit isn’t properly addressed by the customer service representative. Over time, AI will more accurately emulate our cadence, however I believe that concern will be checked by perception of the message.

The funny thing about things we can’t comprehend is that our curiosity guides our understanding. If you talk to a mechanic about his craft, you should prepare for a long-winded diatribe about internal combustion engines.

Even in the less tangible industries like the tech industry, niche blogs and podcasts starring experts help to pump the pulse of fandom to the point where lampooning memes showcasing the industry‘s modern concerns litter message boards.

On the public stage, the emergence of AI photography has caused our connection with reality to become askew to the point of recent accusations that Princess Catherine of Wales had published a photo thought to be the work of AI, that turned out to be a poorly executed photoshop.

What then will become of the children, you may be asking yourself. Will they be prepared for an environment burdened by illusion?

Probably. AI was born from computer technology and our relationship with those devices has become second nature to children when introduced to them at a very young age. Young enough to the point that researchers have found the amount of screen time among children to be alarming.

A strong argument came to be made against children having prolonged computer usage, specifically with issues such as social isolation to attention deficit. It can also be argued that comprehension of the operation of electronic devices at a younger age can result in the early development of digital literacy.

In a 2019 study by the California Science Teachers Association out of Los Angeles, where 200 elementary school students took a 10 week coding course, found that computational thinking among the students has equipped them with essential critical thinking. The students were then interviewed and said they were then able to conceptualize, analyze and solve complex problems found in everyday life as well as with interdisciplinary studies.

What I’ve taken away from this is an adage as old as the human race: that we perceive the younger generation to be less intelligent, but that practical intelligence among that younger generation seems incomprehensible to later generations. To say, emojis and acronyms don’t represent less literacy, but literacy applicable to modern sensibilities.

Still, age isn’t a limitation to digital literacy. Perhaps you know someone who has fallen victim to the desperate pleas of a Nigerian prince, and you may have also noticed that those scams are being replaced by new and unique scams.

Sextortion, or the act of having private nude photos sent to an online love interest only to have those nudes used as an opportunity for scammers to extort money from unsuspecting people, has become commonplace nowadays, with devastating effect to people’s lives. Tragedy has beset a number of young lives, but hope is on the horizon.

Instagram is already taking steps to combat this epidemic, and it can be assumed that other social media outlets will follow suit in short order. We culturally take umbrage with lives taken by their own hand after online scammers, and corporate policy in concert with bureaucratic litigation is already doing its part.

The phrase “sextortion,” despite joining the Merriam-Webster dictionary in 1949, didn’t become a common appearance in the American vernacular until recently. The Nigerian prince phenomenon, however, has been around since the 1990s through Hotmail accounts and AOL instant messenger.

The problem has seemed to dissipate as the scammers’ practices had become common knowledge, albeit slowly. With corporations and lawmakers already taking a stand against contemporary sextortion scams, it’s easy to ascertain that scams will be noticed and alleviated in quicker order than times in the past. We are becoming more adept at developing a familiarity with the weaknesses and inauthenticities of the technology we embrace.

In this generation, we may witness machines taking over the vast majority of our thinking work, and it’s something that could understandably be a threat, however it’s highly unlikely that Americans will be the guinea pigs for digital balance.

Americans are the consumer, whereas the global south tends to be the product. In the case of developing countries, such as India, Brazil, et cetera, the influence of American economics looms large.

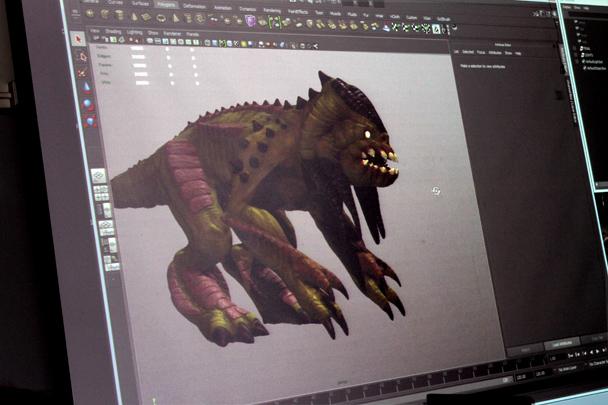

The elimination of overseas employment opportunities for jobs like call centers, animators or CAD drawers will be felt in these countries whereas luxuries like robust savings accounts, commercial development and social safety nets are only pipe dreams.

As the American marketplace becomes less and less reliant on cheap overseas labor due to the application of AI, the economies of the global south will implode. Without the financial flexibility to diversify the economy, the strides being made toward development in these countries will in turn become halted, or worse, negated completely.

As we transition into a world where the volume of everything on the internet can be crammed into an app and trained to produce a desired result, it’s imperative that we evaluate its impact from a level-headed and pragmatic perspective, so that we can avoid acting upon paranoia as well as be able to use the new tools at our disposal to make the world a better place.

Brad C • Jan 24, 2025 at 4:08 pm

worth noting that a big reason people are afraid of ai isn’t an irrational fear or because it’s new and scary, but rather that its corporate use tends to promote unfair labor competition. so many jobs are threatened because it is the latest tool of the managerial class to exploit workers, automate away labor (even if poorly), and be used as justification for layoffs. we’ve already seen the negative impact of its use on search engines and media companies, and artists are rightly up in arms about our work being unfairly exploited.