He is haunted by it everyday.

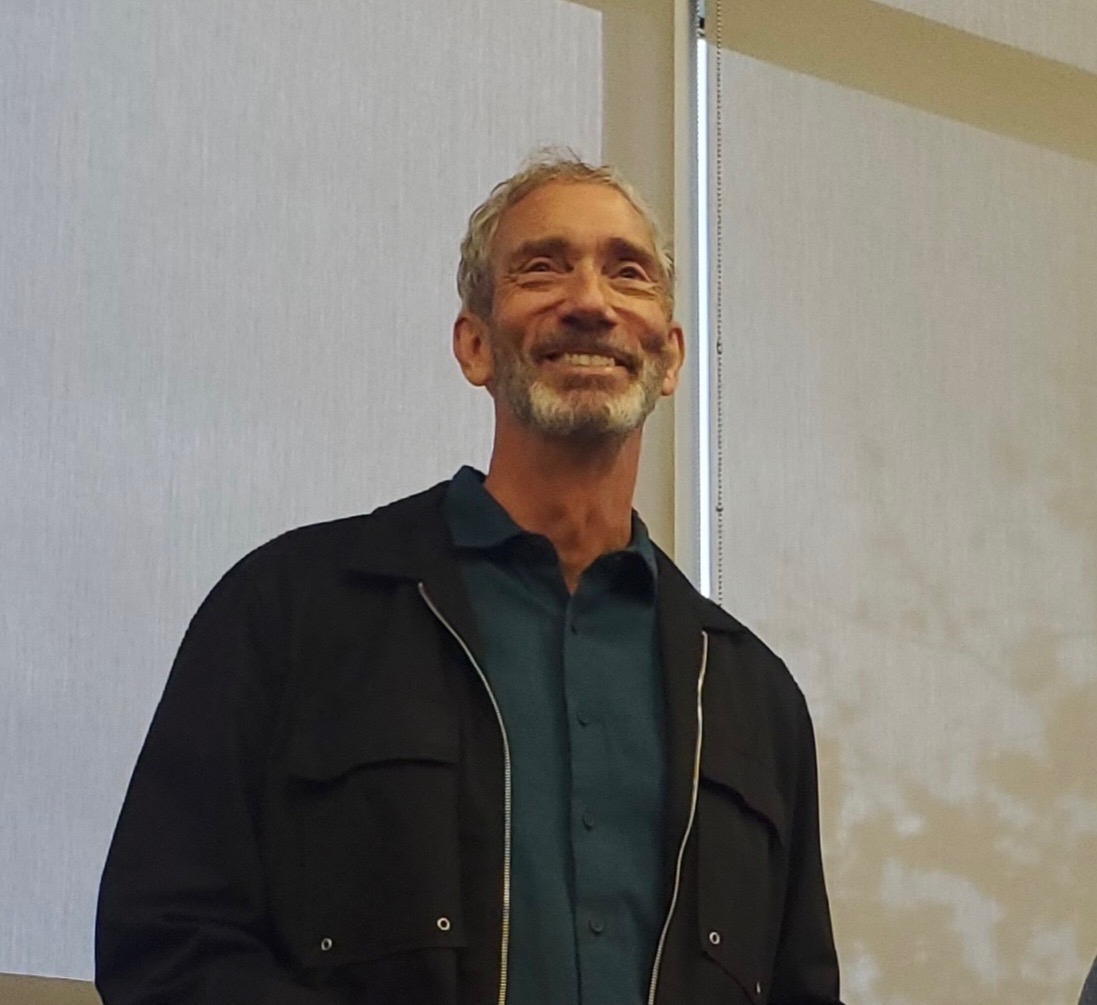

“The boogeyman,” 33-year-old American River College student and former Marine infantryman Daniel Ayers said. “I am always worried (about) when that damn boogeyman is going to jump around the corner and take a shot at me.”

Ayers, like every one in four United States military members returning from deployments overseas according to Wounded Warrior Homes, suffers from the effects of post-traumatic stress disorder.

After graduating from Cordova High School in 1997, Ayers joined the Marines in January 1998 and served in active duty for eight years.

As a member of the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines based at Camp Pendleton, Ayers said he deployed to “some cool places, and some not-so-cool places.”

Ayers, now as a 32-year-old full-time student at ARC, deals with the repercussions suffered from a traumatic brain injury while on active duty.

He now walks with a cane because of physical ailments that resulted from what he says is “wear and tear from jumping out of too many helicopters and kicking in too many doors.”

The cane is deep red and embroidered with the emblem of the Marines. Ayers’ limp and deep, dark eyes show the physical effects of years serving his country.

Years, he says, that were “awesome,” despite leaving him with a disability that overtakes his mind and leaves him a far cry from the physical specimen he once was less than five years ago.

“It was something I was damned good at and something I could identify with,” Ayers said.

Like the unknown enemy behind every door that he kicked in, Ayers says he lives his life in a heightened state of awareness as a result of PTSD.

Even on campus.

“I have to sit in a certain place where no one is behind me,” Ayers said. “I have to walk down the halls and be careful while looking around corners because I am worried who is going to be jumping around the corner.”

That unseen disability plagues Ayers, along with other veterans who are trying to reintroduce themselves into higher education, according to Barbara Westre, an adjunct faculty counselor with the Disabled Students.Programs and Services on campus.

What PTSD Actually Is

PTSD is a set of long-lasting reactions or symptoms that come after exposure to life-threatening events to yourself or to others who are close to you, according to Dr. Brian Engdahl, an associate professor with the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Minneapolis, Minn.

PTSD is not a mental disability diagnosed singularly to military veterans. The repercussions can stem from domestic violence, rape, and time spent in prison. PTSD has also been diagnosed for victims and witnesses of the terrorist attacks in New York City on Sept. 11, 2001.

Engdahl told Ivanhoe Broadcast News in January that PTSD and the trauma results in “unwanted memories, nightmares, flashbacks, or (being) distressed or aroused when reminded.”

Ayers and other frontline veterans returning from war-torn regions were forced to see and do things 99 percent of society never will have to.

Not Dealing With It

Ayers said that the military informed him that he suffers from PTSD when he was medically discharged in 2006. But, because of “the pride of being an infantryman,” he didn’t seek help for his disability.

Rather, he moved back to Sacramento and dealt with the nightmares and memories with the bottle while moving from job to job because he couldn’t hold one down.

“It didn’t work, I didn’t fit in,” Ayers said regarding the four years following his discharge from the Marines. “It’s like a square peg in a round hole — (I) didn’t fit.”

He numbed the pain with vodka and Crown Royal. Going to bars, Ayers said, made him happy because he could let his guard down.

“I was dealing with it by drinking A LOT,” Ayers said. “Trying to forget and trying to numb pain. I was drinking like two fifths a day of alcohol.”

But the booze only intensified the pain of his past.

“Then other stuff would come up later and all you are doing is bottling this stuff up,” Ayers said. “But when the bottle gets too full of all of your emotions, it overflows.”

After several years of hard drinking without medical treatment for PTSD, Ayers came to a breaking point.

“I couldn’t take dealing with it anymore when it was coming up and there (were) times when I was getting really depressed and I didn’t want to fight my battle anymore with my PTSD,” Ayers said. “I was contemplating suicide.”

But, he said, the one person who kept him from taking his own life was his now eight-year-old son Braeden.

“I didn’t want to leave him without a father,” Ayers said. “So I called some family members for help and told them to come and get me. They came and got me and that’s when they took me to the hospital to help me clean myself up and the wounds of what I had done to myself.”

Getting Help

With advice and more motivation than Ayers felt he had at the time, he got help from the years of combat and hard living.

“(My family) got me to mental health while I was there,” Ayers said. “I didn’t want to go, but they got me over there and that is when I started getting help with my PTSD.”

He was admitted into medical care at the VA Clinic in Rancho Cordova and finally began treatment for PTSD.

Now, Ayers works in the Re-Entry Center on campus while continuing his treatment.

“I am learning better ways to cope with my PTSD, rather than run to the bottle,” Ayers said. “Now when things happen, I have better ways to deal and recognize.”

After completing his Associates of Arts at ARC, Ayers hopes to further his education with a master’s degree in vocational rehabilitation. He hopes to give back to those who helped him get to a happy medium in his life and teach others that it can always get better, despite the disability.

“All I want to do is give back,” Ayers said. “And help people. Just like I am doing now — all I want to do is help people starting over and finding them a new direction. I want to help them with a new path.”

horntc@imail.losrios.edu